Pet ownership is a curious thing. It expands our notions of companionship and broadens our capacity to love. It allows us to perceive and experience devotion without the complexity of human discourse. It is a relationship devoid of machination, and one that symbolizes the beauty of affiliation between two creatures. A beauty that is simple, organic, and pure.

So, when you lose a pet, as I did in this particular case, the question became: what is the extent of my devotion? A devotion perhaps not just to the individual pet, but to the inherent concept of pet ownership itself. To me, losing my cat presented a larger question regarding what an owner can and should do, rationally, in the face of frustrating adversity. I suppose for me, the answer was obvious, even if it involved an untenable level of effort. After years of providing a nurturing sanctuary for my cat, changing litter boxes, and cracking open cans of food on a daily basis, I had to ask myself: what exactly was the limit of my effort to search for my cat when she was lost, scared, and in need of my help?

The story begins somewhat simply, if not frustratingly, with an instance of contemptible behavior. I lost Bugs on Friday evening, June 24, 2016. During the course of our attempt to sell our home, we had a private showing scheduled for 4pm that afternoon. A realtor and his clients were to arrive and take a look at our home. It was at this fateful hour that the realtor and his group of guests opened a large sliding glass door in a back bedroom, and Bugs — most likely flanked on both sides by unknown, loud, and generally aloof interlopers — fled through the open door and allegedly “hopped a fence” in my backyard, ascending a flight of fifty (50) stairs to a wilderness replete with cactus, oak trees, brush, sage, and predators of various orders.

Because the realtor was a silent, uninformative dreg who cared not for the disruption of my domestic ecosystem, he said nothing to my realtor (who was present) about my cat running off. No one knew that Bugs went on this fearful adventure. In fact, it was not until Saturday morning that Bugs’ absence was apparent. I searched the normal hiding spots — behind the bed, in closets and cabinets, and underneath every conceivable object and corner. She had not come out to eat, and if anyone knew Bugs’ temperament, this was abnormal. She is easily about 16 pounds, eats excessively, and uses the litter box more than I can quantify. In the absence of any of these behaviors, it was clear that Bugs was gone.

My search shifted logically to the exterior of the home. I waded through ferns, shrubs, ivy, and everything that surrounded my home. Nothing. This process of searching the same physical areas continued unabated throughout the course of Saturday, that evening, and into Sunday when I was finally informed that the visiting realtor from Friday had allegedly observed Bugs “jump the back fence.” Upon hearing this witness account, I immediately discredited it. Bugs is approximately 15 years old (i.e., geriatric in cat years); she does not jump; she has trouble climbing up my son’s bed at night for support; and, she had never ventured outside the doorframe for longer than a minute.

Equipped with this historical knowledge regarding her tendencies, it was inconceivable that Bugs would have scaled a 7 foot fence and ran up 50 stairs to the mountain. More likely, in my mind, was the fact that she had found a hiding spot nearby at the neighbor’s house and was laying low under a hedge. Nonetheless, I trekked up the stairs and commenced a broader search that would now encompass gnarled cacti, blistering 100 degree heat, poison oak, snake holes, wild bushes, and shrubbery of every conceivable kind.

“This is impossible,” I exclaimed, in a fit of guilt-ridden resignation. If she had traversed up here, the odds of survival would be minimal, at best. There are too many areas, the mountain is expansive, and predators (such as bobcats and coyotes) have been known to frequent the area. Hungrily so.

At that point, I subscribed to the convenient explanation(s) — either that Bugs “was killed by a coyote,” or that she was sick and “wanted to die,” thus resulting in uncharacteristic wandering. Both of these alternatives were suggested by many who heard the story of Bugs’ impromptu escape. To be sure, they were fair and possible conclusions, but they were unsupported by anything concrete. My cat did not appear ill prior to her departure (but for her old age), and I was not willing to import myself into Bugs’ consciousness and presume to conclude that she had executed a dramatic escape in order to die a romantic, alienating death away from the observing eyes of her woebegone owners.

The main factor, though, was that I had invested approximately 15 years into this cat’s life, and Bugs was in a heap of trouble. Unquestionably. So, I cast aside the convenient explanations and the psychological presumptions regarding her rationale for leaving, and I was going to keep looking. Especially now, during what had to be the most critical time. The more time that passed, the prospect of Bugs’ survival in this environment would lessen. This reality hung over me like an anvil.

On Sunday evening, after hours of searching on the mountain above my house, I turned to the Internet for support. I read all of the attendant wisdoms and anecdotes: that indoor cats would invariably be hiding close to home, that I should tap her cat bowl with a fork outside the house, search bushes, and call out to her, and other rather obvious suggestions such as posting signs and informing neighbors. Undaunted, I searched the same areas around my house that evening and found myself morbidly drawn to a stretch of ivy along the side of my house, where an unfortunately rank odor of death was emanating. Of course, my heart sank. This was not a favorable equation. Missing cat + smell of rotting animal flesh = potentially bad result for Bugs. I scoured the ivy with a flashlight leaf by leaf, expecting to find a Bugsy corpse, or some part of her. But I didn’t. Instead, I found the sanctuary of a woodland rat species, nestled in the upper reaches of the ivy, where one had died and was rotting ignominiously. Sickened by this collateral discovery, and certainly resolved to eradicate these pests another day, I was at least thankful that I didn’t locate poor Bugs pushing up the daisies.

Later Sunday evening, I read about Ms. Annalisa Berns of “Pet Search and Rescue,” based out of San Diego. Ms. Berns is a private “pet detective,” who has made it a career to rescue lost pets. Though I thought initially that pet detectives were simply the product of lore or comedy, it was in fact quite real, and Ms. Berns’ devotion to this trade was even more real. After researching her curriculum vitae and discovering that she had been written up in Oprah Winfrey’s “O” Magazine, I decided to reach out to her and get more information. A simple email to her that evening resulted in a swift response, and by 930 p.m., I was in a full-fledged discourse with Annalisa about her services, its cost, and time frames for a potential search. She informed me that she could be at my house by 630 a.m. the following morning. I retained her and decided that locating my terrified, scared kitty was paramount. Plus, if I didn’t at least attempt to retain Annalisa, perhaps I’d feel eternally guilty for not just trying. (Guilt is a real bitch when it comes to losing pets.)

Before retiring for the night, I recalled those mischievous days in my youth when I was intrigued by military gear such as dtnvs, and other seemingly sophisticated search tools. This led me to a specific product, released by the company “Flir”. In plain English, it was basically an optical device enabling an individual to detect heat signatures of animals and humans at a distance of 100 yards during the night. It is called the Flir TK Scout Thermal Monocular. If anyone recalls the film “Predator,” this is similar in terms of the imagery. Looking through a Flir would produce a similar image: that is, a lot of black and undefined areas such as plants, but with all human or animal subjects illuminated in a hot, fiery, reddish hue. Because of my inherently dorky nature, and because it could offer me a potentially useful tool for nighttime searches when it was cooler out, I purchased the Flir TK Scout, and eagerly anticipated its short order delivery by Tuesday, June 28.

Monday mornings in my world are about the vicissitudes of lawyering. I typically wake up with the anxiety of a daunting amount of work, and find that the sanctity of the prior weekend is almost entirely lost within the first few moments in which Monday has suddenly presented herself with an array of responsibilities. Except, on this particular Monday morning, June 27, 2016, there had been no rest. The weekend had been defined by cycles of guilt, tears, impenetrable heat, and a frustrating level of uncertainty over how to locate Bugs. Annalisa arrived at 630am with three search dogs and a set of determined eyes. Her attitude and demeanor were infectious and positive. Only hours after emailing her, she had driven from San Diego and was ready to commence the search. Perhaps Bugs had a chance.

The first order of business was to obtain a scent sample of Bugs’ fur. I listened to Annalisa’s preliminary instructions, which included details about the normal course of a search, staying out of the dogs’ way, the necessity of contacting and advising neighbors of our impending trespasses into their yards, and other protocols. I directed Annalisa to the area behind my bed where Bugs would sleep quite often. As expected, clumps of Bugs’ fur remained in that spot, and within only a matter of seconds, Annalisa had the organic, forensic prompt that she needed to set the search dogs into motion. She gathered the fur into a Ziplock bag and indicated that she could “refresh” the search dog throughout the course of the search by waving it in front of their noses. Only one dog was used at the outset of the search, so as to not taint the others, who remained resting in Annalisa’s truck in a shaded area.

When she presented the dog with the sample fur, the dog darted down the hall. With pinpoint immediacy, the dog traveled to the sliding glass door in the back bedroom and signaled Annalisa to open it. Annalisa opened the door, and the dog proceeded straight to the back fence which led up the flight of fifty stairs. It gave Annalisa the signal. Up. I stood, looking amazed. The dreg idiot realtor was right. Bugs had indeed jumped over the fence and went up the stairs to No Man’s Land. Though excited by the dog’s confirmation of this fact, my heart sank, because I knew what it meant. It meant, specifically, that the search for Bugs was going to necessitate rigorous hiking and searching through the outer edges of the Glendale Hills, where the heat was fierce, and the topography was fiercer.

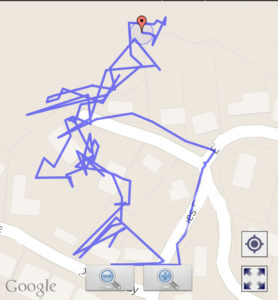

Annalisa instructed me to wait behind so that I would not distract the dog. I stood at the base of the stairs for 45 minutes as she followed the dog through bushes, hills, and other unknown areas. Soon thereafter, Annalisa texted a photograph of the dog (seen above), perched near a neighbor’s home on the other side of the hill. She also texted me a preliminary GPS map, documenting the trajectory of the search dog, which I shall post below. It basically looked like a squiggly line drawn by my 3 year old daughter. Her instruction was to contact the neighbors and indicate that we were searching in the area.

The first neighbor was not home, and the dogs continued their zig-zag path across the hill into other neighbors’ yards, compounding my need to knock on multiple doors. I made my way to the bottom of the street behind my house, and started to contact neighbors. They were generally agreeable with my search efforts, though most seemed perplexed by the notion of a local homeowner enlisting a “search dog” on a Monday morning in order to locate his lost cat. Whatever. The standard response was typically, “the cat is probably gone with so many coyotes in the area.” As such, it was a difficult balance attempting to deflect opinions about my futile efforts, while also informing the neighbors that I was committed to trying and would appreciate cooperation. No one was resistant to our search efforts, and Annalisa continued searching various surroundings without impediment, as reflected in the following image.

It was at this juncture that the neighbor who lived behind me on the hill arrived home. I contacted her and informed her about the search. She introduced herself as Sue. Wearing ankle weights, Sue seemed busied at first, but she soon melted when she realized that we were not solicitors. With her memory jogged, she indicated that she had in fact seen Bugs a day or two prior, attempting to get into her back door. She described the exact physical characteristics of Bugs, along with her unmistakable green eyes, and informed us that Bugs had been cowering in fear. (Cue crestfallen reaction and biting tears.)

This would prove to be the best clue regarding Bugs’ physical whereabouts. Annalisa used all three search dogs throughout the course of the morning, and they independently and uniformly identified a similar circumference of physical territory where Bugs’ scent had been left. The home where Sue saw the cat was at the dead center of this target area.

Though Annalisa’s hopes were high, the circumference of potential search areas, coupled with the fact that one of the dogs sniffed her way up a nearby fire access road along a distant mountain, left me with a sense of impending dread. Not to be discouraged, Annalisa informed me that this was a discrete area and to remain steadfast in my efforts, because the dogs did not indicate to her that there was a scent of death. To that end, Annalisa encouraged that I put up signs and distribute fliers. Most importantly, she advised me to continue walking along these same paths and regions, in order to leave a trail of my scent, so that Bugs – if still alive and hiding in the area – would perhaps detect my scent and be able to navigate herself back home. Monday’s search with Annalisa concluded just before 11 a.m., when the heat had already reached a deadening mark of approximately 95 degrees. The dogs were tired, and my spirits were shrunk. After kindly receiving some poster boards and a huge Sharpie marker from Annalisa, I drafted several large signs and taped them around light poles in the neighborhood. “LOST CAT, PLEASE CALL.”

Though I went to work after Annalisa’s departure, my thoughts were never far from Bugs. I empathized with her plight. I envisioned her buried and ensnared in a thicket of dense hot brush, up along a mountain, meowing and wondering how to get home. Every second that I sat at my desk, I felt an augmenting sense of responsibility in my guts to continue searching. To not give up.

Yet, Monday night’s search was fruitless. I scoured the mountain along with all of the points of interest noted by the search dogs. Nothing. By Tuesday morning, my spirits had dwindled to desolation, and I felt resigned to the possibility that I had to learn to let go. Nonetheless, I went for a walk early in the morning, and re-traced all steps up my hills, down along the street behind my house, and into a storm drain wash that exists at the end of a cul de sac, where there are no homes, and instead the expanses and wooded areas of the hills.

By Tuesday afternoon, my Flir TK scout thermal monocular had arrived in the mail. If anything, I felt a moderately renewed sense of hope that I could at least use this tool to locate her during the nighttime hours. I got home early from work and distributed 100 fliers to local residents, which offered a short narrative about Bugs, a couple of photos, and the promise of a reward. I felt extremely puny and defeated when certain residents were outside of their homes at the time of my distribution, and they assumed I was a solicitor. I informed them of my lost cat, and that I was searching. Most people simply offered condolences, knowing that the area was intricate and impossibly treacherous. Furthermore, the heat was blistering, my energy reserves were depleted (i.e., I looked like death, or death’s cousin), and I was developing a sore throat. That night, after a brief rest, I ascended my steps and began learning the intricacies of the Flir TK Scout. I scrolled through its various settings, viewing the nighttime terrain in a variety of colors and heat sensitivities. It was all extraordinarily interesting from a technical standpoint. But, it was completely uninteresting emotionally. Cool gear; no Bugs.

Wednesday arrived, and with it was a sense of diminishing resolve. I knew I could not continue searching at this pace. It was unsustainable. Nonetheless, I returned home from work and hiked along the hills for 2 hours, to a further extent than before. I hiked up a fire access road through thickets of dangerous brush, peering down into neighbors’ back yards, attempting to avoid perilous patches of poison oak.

On my way home, I stopped uncharacteristically atop the hill in back of my house and sat in a chair. A chair had been left there by a neighbor for bird watching purposes, and/or other voyeuristic viewing pleasures. I never sat there before. It was really quite pretty though, and the birds were sonorous. I had always ignored those dirty chairs, never electing to absorb and listen to the environment. Though sitting there was peaceful, I became morbidly sad. All of this goddamn effort was sinking in. For what? I felt that I had let Bugs down, though I knew consciously that I was putting in more effort than anyone could have anticipated.

For some reason, that night, after putting the kids to sleep, I thought I would go out one more time with the thermal monocular. What the hell. I paid for the damn thing, and paid for a search dog to give me a target area, so why not go again? To give myself a chance. To give Bugs a chance. To increase my frequency in the area and to increase at least the chance of seeing something. I took my backpack, a flashlight, and the monocular and headed up the hill. After searching through the leaves and the cactus very slowly, I approached Sue’s home at the top of the hill. I stopped. I sighed. I looked down along a series of landscaped rocky steps, and there was Bugs. Laying there. Meowing.

Holy Bugs!

I didn’t know what to do. I approached her slowly, and she darted off. She was out of sight. I contacted Sue immediately, asking if I could poke around throughout the backyard, as I had just spotted Bugs. I was frustrated, but exhilarated. She granted me carte blanche, and the search was on. Thinking that Bugs was in a starved and frightened state, I wanted to get something to bait her. My mind was racing. So, I gambled and decided to leave the area to retrieve Bugs’ cat bowl and get some food. It would take approximately 5 minutes to retrieve it, but I figured that she was now at least somewhat confined to a certain geographical area and would be within earshot when I returned. Hell, maybe she had been there the entire time for 5 days. Who knows. But, I saw her. Let’s roll with it.

I returned with the feeding bowl and used the thermal monocular to try and locate her position. I couldn’t locate her, but instead, I managed to see her glowing set of green eyes when I used my flashlight in a new direction. She was 15 feet away on the other side of Sue’s back patio. This is good. I moved slow and attempted to bait her with the bowl, but unfortunately, she darted off once again.

I pulled out the monocular and located her 25 yards away, hunkered down in a thicket of weeds. I sighed, and realized I was dealing effectively with a new and different animal. It was Bugs, to be sure, but it was the wild, scared and feral version of my little companion. As a result, I decided that I would engage in a prolonged stand-off, in an effort to have her remain as calm as possible.

I sat on the ground and spoke to her in soft, calming tones. “Hey, Bugs, how ya doin?” I whistled and sat in the dirt, not really seeming eager. Yet, I inched forward at a snail’s pace, constantly rattling the bowl, ensuring that she would not get freaked out and dart off again. This incremental process continued for 40 minutes until I got within an arm’s length of her. Though I wanted to leap at her, I figured I would just keep it calm. She was terrified and looking left and right for potential dangers, but I kept her focused on the bowl and my voice. Once I could reach my hand out slowly, she smelled my hand, and her defensiveness immediately vanished. She walked straight into my arms.

I grabbed Bugs and clenched her as comprehensively and strongly as possible. Leaving all of my gear on the ground, I walked her across the crest of the hill, down 50 steps, and back to the house, kissing her the entire way.

It was five days of searching in deadening heat and adverse conditions. Five days of vacillating emotions. Five days of the unknown. Five days of weird justifications and thoughts. They say a cat has nine lives, and that cats often display curious behavior. It is so true. But what is rarely discussed is the owner’s response to a pet’s dilemma. What to do, how to do it, and in some cases, whether to do it at all. I submit that animals are family. This should not come as some groundbreaking observation. They are part of the peaceful, environmental fabric that you have cultivated in your home. To abandon your animal with immediacy and with resort to convenient psychological presumptions about their intent is to abandon your commitment to the love and affection that you both have forged. I could never blame anyone for doing even 1/10th of what I chose to do. Everyone has different issues, time commitments, pressures, limitations, and levels of resolve. But I can faithfully report that love and determination, in its rawest form, can produce beautiful results.

This was Bugsy’s Great Adventure, and I am ecstatic to see that she is purring next to my son at night, assured on some innate level, that she is loved.